In a City Under Lockdown, a Race to Deliver Anti-HIV Drugs

Chen Sheng counted the white pills that remained in his medicine bottles. The clock was ticking: Within 12 days, he would run out of anti-HIV drugs. His partner’s stock was even more depleted, with just enough left to last one week.

The couple, both 53, were diagnosed as HIV-positive in 2018. Doctors warned them to medicate according to a strict regimen or face increased viral loads and drug resistance. And so, aided by smartphone alarms, they take their pills at set moments, undergo regular medical checks, and make sure to order new stock one month in advance.

But the outbreak of COVID-19 and subsequent lockdown in Wuhan, the city in central China’s Hubei province where Chen and his partner live, have interrupted their meticulous schedules. With health services preoccupied fighting the epidemic — which has sickened more than 80,000 patients and killed over 3,000 in China as of Thursday — thousands of Wuhanese who rely on medication to stay healthy are locked inside their residential compounds while they watch their supplies dwindle.

As early as Jan. 26, three days after Wuhan went into lockdown, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) released a notice requiring local China CDCs and HIV service providers to guarantee people’s access to anti-HIV drugs. Nevertheless, nearly one-third of HIV-positive people in China still said restrictions on movement were affecting their HIV treatments, according to a survey among over 1,000 such people by United Nations AIDS agency released in February.

When Chen’s supplies began to run low, he looked into what it would take to reach the one hospital where he and his partner can pick up their medication. To get an exit pass necessary to leave his residential compound, he would have needed a certificate from his local China CDC stating that he is HIV-positive. But to get to the China CDC and receive such a certificate, he would need an exit pass. If he somehow managed to break out of this bureaucratic Catch-22, he’d still need to make the 35-kilometer journey to the hospital either by foot or by bicycle, as other transportation methods had been suspended.

Crucially, the process would inform the people in Chen’s neighborhood that he and his partner live with HIV, something they had planned to keep secret to avoid being stigmatized. Chen’s partner fears being fired by his government-affiliated employer.

“I really don’t want to bother the government, the medical staff, or the social workers, because I know they are all busy fighting the epidemic. So I think I can bear all the difficulties caused by the lockdown: I can eat less when we cannot go get groceries, and I can take cold showers when we’re running out of gas. But I can’t stop taking the medicines,” Chen, choking up, tells Sixth Tone in a phone interview. “That will take my life.”

Volunteer Networks

Since late January, Huang Haojie, who works at the nongovernmental organization Wuhan LGBT Center, says he’s received hundreds of calls and messages from people like Chen who were in dire need of their prescription drugs. It made him realize how acute the situation was. “As far as I know, many people have already run out of medicine,” he says.

The first solution Huang thought of was to connect people living with HIV in Wuhan with those outside of it, allowing people unaffected by lockdowns to share their extra doses. Dozens of people responded, yet Huang realized this was not nearly enough. At the time, Wuhan residents could still move around the city, despite a lack of transportation options, and Huang called on volunteers to give rides to people with HIV so they could pick up their medicine at Jinyintan Hospital, where most HIV-positive people in Wuhan, including Chen, receive their treatment.

When MJ, who requested anonymity because of the nature of his volunteer work, drove to meet his first passenger, he remembers feeling nervous. Jinyintan Hospital is also designated to receive COVID-19 patients, and, afraid of infection, he decided to wear three surgical masks.

MJ’s first passenger was quiet, polite, and anxious. The passenger had planned to pay a short visit to Wuhan before the Spring Festival but was now locked in the city, unable to return home. “Because of the coronavirus, we were both vigilant,” MJ recalls his first trip. “I opened the windows during the whole trip, we kept the largest distance between us, and we rarely spoke a word to each other.”

MJ was sympathetic to passengers who were late, figuring they were probably trying to get away from their families without telling them why. He made sure never to ask for personal information, knowing passengers would want to stay anonymous. Still, it caught him by surprise when one passenger told him he’d delete his contact information as soon as possible. “At first I felt a little bit strange and offended — ‘is that a big deal?’ But later I sorted it out: everyone has their secrets,” he says.

“To be honest,” MJ says with a pause, “I used to have high-risk sexual behaviors, and (fearing being HIV-positive) I did some medical checks ... So to some extent, I can imagine how helpless and desperate those patients might be.” MJ says. “It’s really, really not easy to live with HIV and that secret.”

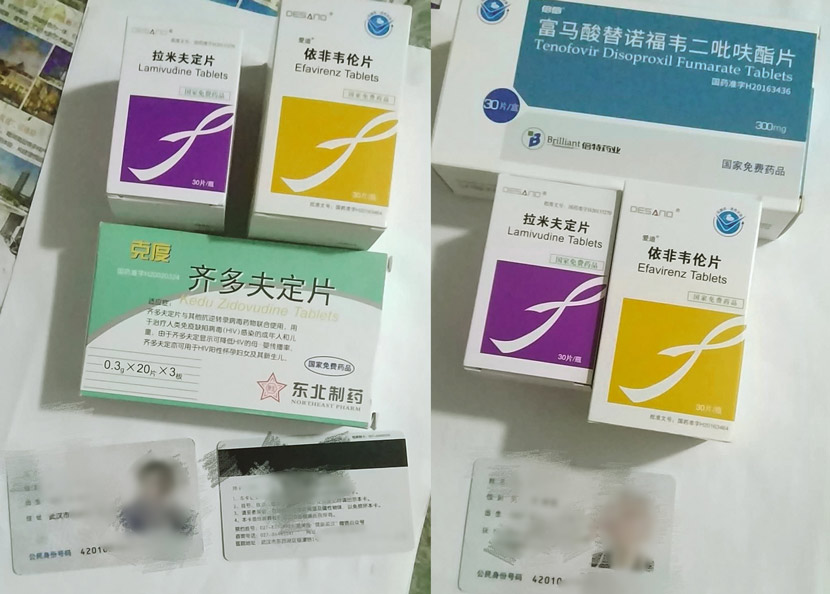

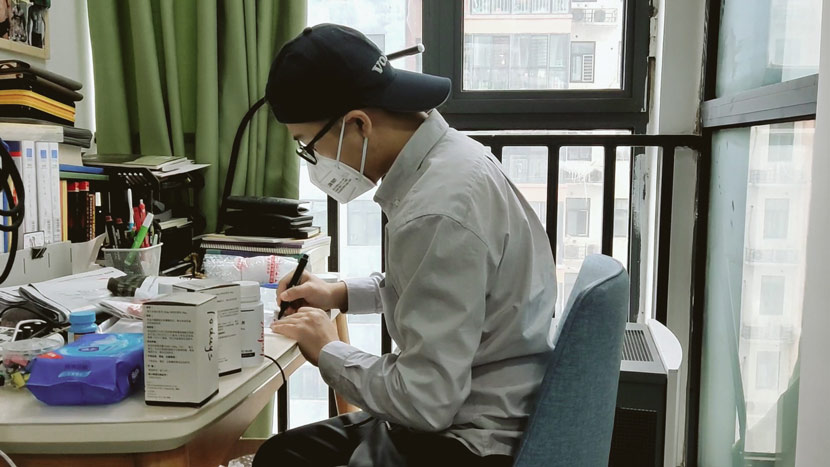

Such trips quickly became impossible, however. Since mid-February, stricter measures have forbidden Wuhanese from leaving their residential compounds. Instead of chauffeuring, volunteers like MJ — who have secured exit passes — have switched to picking up medicines on people’s behalf, including for Chen and his partner. Armed with stacks of paperwork, they help up to 65 people a day, making trips to the hospital pharmacy before delivering the medicines to the LGBT center’s office, where the medications are collected by one of the few courier companies still operating in Wuhan.

While spending more than eight hours a day in Jinyintan, MJ and other volunteers have limited resources to protect themselves — they don’t have enough respirators and rubbing alcohol, let alone protective goggles or suits. They dare not eat the provided free lunches inside the hospital. “I always drive to a place several kilometers away from the hospital, close all the doors and windows, disinfect my hands, and then I can feel relieved enough to have the meal,” MJ says.

Despite the best efforts of volunteers like MJ, many people living with HIV have not been able to receive help, especially those who live in Hubei but outside of Wuhan. Subject to the same restrictions but not the same attention, they have chosen to walk an entire day to pick up their prescriptions, to ask for police assistance, or to simply remain quiet.

Calling for help in public, however, can backfire. On Jan. 24, a Weibo microblog user “Makeup Boy Zou Junxi” from Tianmen, a city in Hubei that had also gone into lockdown, wrote that he only had eight days of anti-HIV drugs left. The post worked, but had unintended consequences. To verify the situation, police visited his family and revealed Zou’s status, which he had kept from them. Zou also suffered abusive comments below his post, which he deleted soon after.

Same Drug, Different Diseases

When Andy Li shared on Weibo that he had 40 boxes of the anti-HIV drug lopinavir/ritonavir he was willing to part with, the first person to respond was not someone with HIV, but a doctor in Wuhan whose CT scan had shown signs he had been infected with the novel coronavirus. Gradually, more and more people, including doctors and nurses working with COVID-19 patients, came to him to ask for the tablets that are marketed to treat HIV, but have been found to be effective against the new coronavirus, too.

Li, who himself was diagnosed as HIV-positive in 2012, developed a social network for sharing anti-HIV drugs in late 2017. But it wasn’t until this year that his network took off, mostly because of the off-patent medicine lopinavir/ritonavir, also known as Kaletra and Aluvia. On Jan. 23, respiratory specialist Wang Guangfa — a medical expert sent to Wuhan for inspection who was infected during his visit — said that lopinavir/ritonavir brought down his fever in one day. Though there is as-yet no cure (or vaccine) for COVID-19, lopinavir/ritonavir is one of the potential treatment options recommended in the government’s national guidelines.

“For HIV-positive patients, Kaletra is not their only choice,” Li tells Sixth Tone. “Donors share their extra Kaletra pills, because they have alternatives. But for COVID-19 patients, it could be the hope to save their lives.” Li himself stopped taking Keletra four years ago because of the drug’s strong side effects, but sought out supplies abroad so he could gift them to COVID-19 patients.

“There’s quite a difference between helping HIV patients and COVID-19 patients,” says Li. “I can tell whether HIV patients need the medicine by a quick chat, and nobody will wrongly take them. But for COVID-19, I have to be more careful.” To make sure the drugs get to the right people, Li will ask for every patient’s medical information and make sure they understand the potential side effects. Also, since the guidelines state that lopinavir/ritonavir is only effective for patients with mild symptoms, Li won’t send the medicine to people whose disease has progressed beyond that. Turning down such requests is heartbreaking, he says.

Some have doubted whether what Li does is helpful, as the drugs have strong side effects but unclear benefits. Recently, doctors at the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center published a peer-reviewed paper on treatment outcomes, stating that patients with lopinavir/ritonavir treatment did not recover faster than those who were not given antivirals, while a WHO-backed clinical trial in Wuhan is still underway. Li read the report but decided to continue. “I will strictly follow the national guideline and only stop when lopinavir/ritonavir is removed,” he says.

This campaign has allowed Li to get to know more people living with HIV — they are different ages, come from different cities, and work for different industries. “Everybody has their own special lives. HIV/AIDS shouldn’t be the only label to identify them with,” he says.

Chen, who received the volunteers’ package of medicines on March 1, holds similar views: “No matter if you’re a COVID-19 patient, a relative of someone who passed away, a regular person, or someone living with a chronic disease like me, we’re all victims of this epidemic.”

Editor: Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Header image: Volunteers collect anti-HIV medicine at the pharmacy of Jinyintan Hospital in Wuhan, Hubei province, February 2020. Courtesy of MJ)